Crowned Before We Can Think: How Children’s Books Normalise the Monarchy

Let's examine children's books about royalty, how toxic they are, and what alternatives we could publish instead.

12/24/20257 min read

When we think of propaganda, images of North Korea, the Soviet Union, or wartime “Dig For Victory” posters often come to mind.

Yet the British establishment has long mastered a quieter, more effective form of indoctrination: subtle, constant, and wrapped in charm. What appear to be harmless, colourful children’s books are often powerful tools for introducing young British citizens to a harsh political lesson — that some people are supposedly born superior, deserve more wealth and respect than others, and that this inequality is not only natural, but something to be celebrated.

These books are not neutral. They shape how children understand power, hierarchy, and their own place in society.

So what are the common themes in these wolves dressed as lambs? Why are they so effective? And why is recognising these patterns a vital step in resisting indoctrination?

1. Early Political Socialisation Through Storytelling

Children’s books are often a child’s first encounter with political and social hierarchies.

Stories about kings, queens, and princes introduce ideas about authority long before children are able to question or critically evaluate them. Because these narratives are framed as “fantasy,” “heritage,” or “tradition,” their ideological messages frequently go unchallenged.

Example:

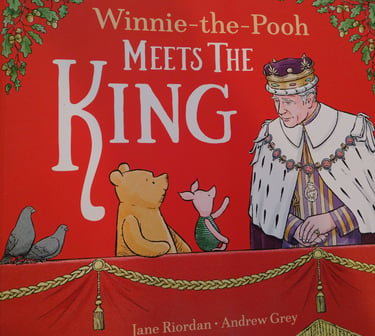

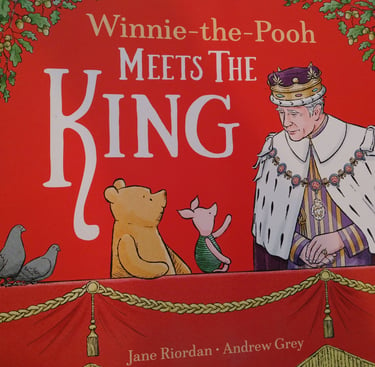

In Winnie-the-Pooh Meets the King by Jane Riordan and Andrew Grey, children are shown royal guards, crown jewels, and cheering crowds. The crowd excitedly shouts, “Three cheers for the King!”

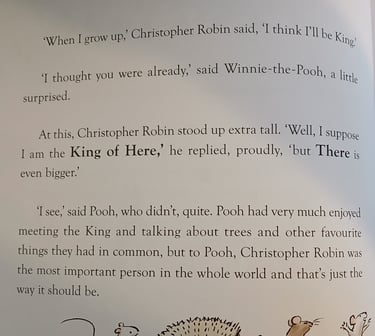

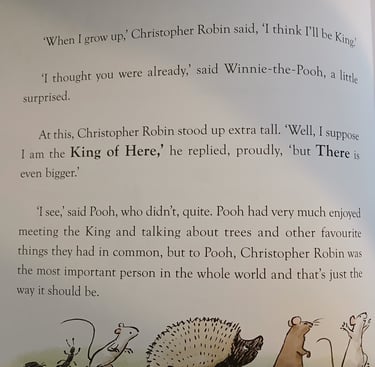

The irony goes unexamined when Christopher Robin declares, “When I grow up… I think I’ll be King.”

The final pages present “interesting facts” portraying Charles as a heroic figure — highlighting his dive to see the Mary Rose wreck and claiming he “owns” all whales and dolphins in UK waters — without any context or critique.

2. Monarchy Presented as Natural and Benevolent

Royal power is typically depicted as inherited, unquestionable, and morally justified.

Kings and queens are shown as kind, wise, and destined to rule, reinforcing the idea that hierarchy is natural rather than constructed. Rarely, if ever, do these stories explain how monarchies historically acquired or maintained power — through violence, conquest, and exploitation.

Example:

Queen Elizabeth – A Platinum Jubilee Celebration (a book distributed to every primary school child at a cost of millions to the taxpayer) presents Elizabeth as a caring mother, hardworking figurehead, and tireless champion of charity.

Union flag bunting fills every page as “granny” toasts “Her Majesty’s 70th Jubilee.” Children are given a glossary featuring terms like British Empire, National Anthem, and commemoration — yet there is no mention of colonial violence, empire, or why many countries sing about their people and land rather than asking a god most Britons no longer believe in to save an unelected billionaire who hid wealth in offshore accounts.

4. “Good Rulers” vs. “Bad Rulers” as Moral Distraction

Political problems are framed as the fault of bad individuals rather than unjust systems.

The solution is almost always replacing a bad ruler with a good one, reinforcing faith in monarchy rather than encouraging children to question inherited power itself. Concepts like accountability, collective governance, or democracy are quietly sidelined.

Example:

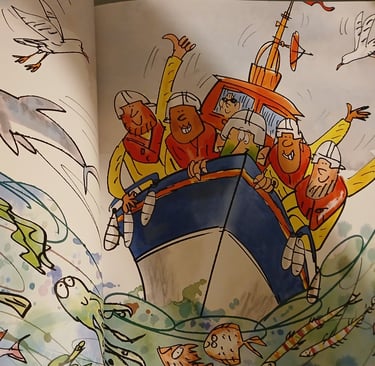

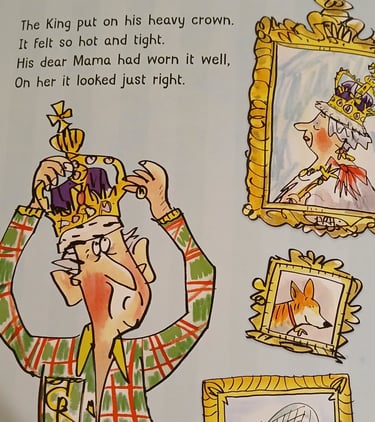

In The King’s Hats by Sheila May Bird, Charles is depicted as overworked and insecure, worried he cannot live up to his “extraordinary” mother. We see him dancing in gardens, donning different hats on royal visits, even wearing a helmet while promoting the RNLI.

Children are not told that the Windsors profit from the charity via duchy land — land that belongs to the British people. Instead, a diverse crowd showers Charles with flowers, chanting, “Kings are brave.”

Children should be taught that bravery looks like being sent to war to earn medals, working through cancer because you can’t afford time off, or becoming the first in your family to gain a degree — not inheriting privilege.

3. The Erasure of Class and Inequality

Fairy tales glamorise palaces, luxury, and noble lifestyles while erasing the labour and inequality that sustain them.

Ordinary people are background characters — servants, peasants, or comic relief — rather than individuals with autonomy or political agency. Poverty is framed as an individual misfortune solved by luck or marriage, not as a systemic injustice.

Example:

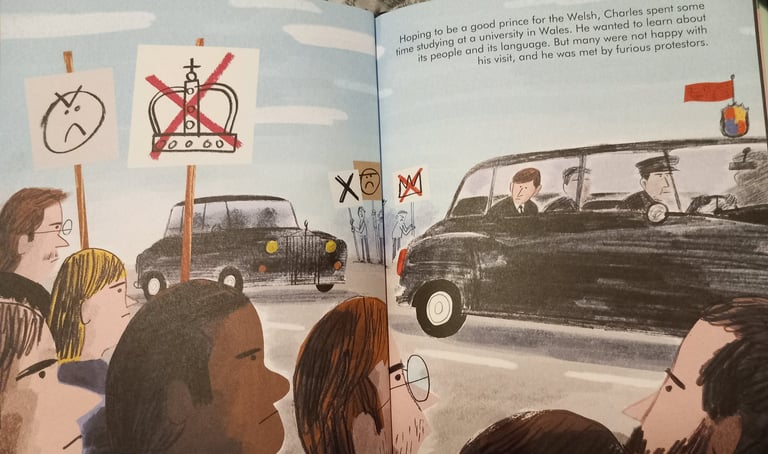

In Little People, Big Dreams: Prince Charles by Maria Isabel Sánchez Vegara, Charles is portrayed as a misunderstood nature lover, shunned by the “mean people of Wales.”

Children are not told about his enormous carbon footprint, his attempts to undermine the fox-hunting ban, or that the title “Prince of Wales” is rooted in subjugation. Wales does not need a prince — least of all an English one.

7. Cultural Soft Power and National Identity

Royal children’s books function as soft propaganda, preserving reverence for monarchy through nostalgia and emotional attachment.

That attachment often persists into adulthood, shaping attitudes toward real-world politics.

Example:

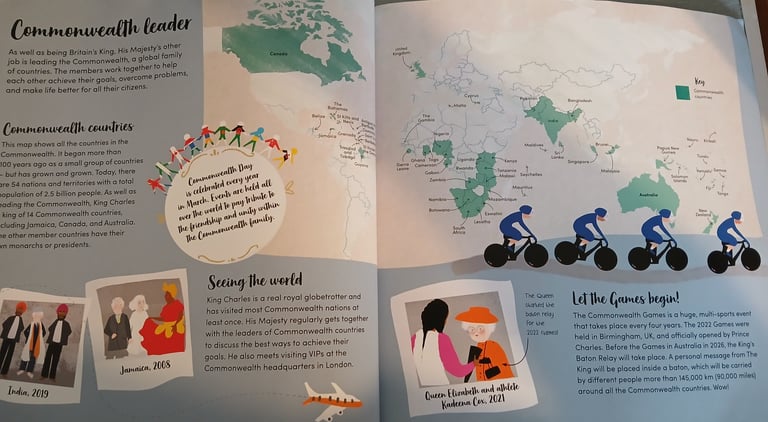

In King Charles III by Andrea Mills, the myth of royal charity dominates. Children learn about Charles’s “wonderful idea” to set up the Prince’s Trust using his “own money,” ignoring the reality of donor funding and celebrity endorsement.

The Commonwealth is similarly sanitised. Photos with people of colour are used to distract from the brutal history of empire — and the royal family’s refusal to apologise for its role in slavery.

5. Destiny, Bloodlines, and the Myth of Merit

Royal characters are often “special” by birth, subtly undermining values of equality and self-determination.

Even when protagonists begin as commoners, their reward is assimilation into royalty rather than transformation of society.

Example:

In Mr Men and Little Miss: The New King, the town is painted and polished ahead of Charles’s arrival. Everyone wants to sit with him at the banquet — especially Mr Snooty, of course.

The book celebrates deference while ignoring the labour of painters, cooks, cleaners, drivers, and servants who make royal spectacle possible.

6. Gender Roles and Royal Idealisation

Princess narratives frequently reinforce passivity, beauty standards, and romantic dependency.

Female power is symbolic or relational — achieved through marriage rather than political agency — reinforcing traditional gender roles alongside monarchy.

Example:

In Little People, Big Dreams: Queen Elizabeth, young Elizabeth falls in love with “a charming prince named Philip.” There is no mention of his racist remarks or infidelity.

Elizabeth is portrayed as beautiful, hardworking (“it was exhausting,” page 16), yet effortlessly balancing queenship with grandchildren and corgis. Lines like “Maybe it was not her childhood dream, but she was the queen the people dreamed of” normalise pressuring royal children into lifelong roles — and the idea that Britons should feel lucky to have an unelected head of state.

Other Dishonourable Mentions

The King’s Coronation Sticker Book (Marion Billet): Children dress the King for his golden carriage but learn nothing about where the crown jewels came from.

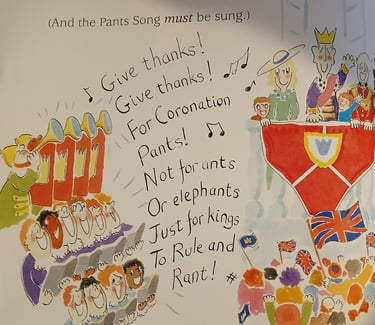

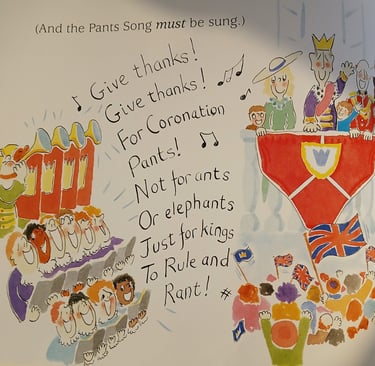

The King’s Pants (Nicholas Allan): Charles is transformed into a bumbling, loveable grandfather who sends out a taxpayer-funded search team for his missing trousers. Humour is a powerful lubricant for injustice.

First Royal Words (Andy Passchier): Children relying on food banks are taught words like “state banquet” and “gold state coach” instead of “greed,” “inequality,” or “nepotism.”

Amazing Facts – King Charles III (Hannah Wilson): The book admits that no one knows what Charles discusses weekly with the Prime Minister — a rare moment of honesty about a profoundly undemocratic system.

Why This Matters

Stories shape what children see as normal, fair, and possible.

When monarchy is repeatedly framed as magical, just, and inevitable, alternatives become difficult to imagine. Critical engagement doesn’t require banning books — but it does demand context, diversity, and questioning.

Toward Better Children’s Literature

As republicans and as citizens who want better for young people, we should support stories that:

Question authority and hierarchy

Emphasise collective problem-solving

Present leaders as accountable and replaceable

Explore power without glorifying inherited rule

Next year, Greens for a Republic plans to crowdfund a children’s book offering real alternatives.

Ideas in development include:

The Girl and the Princess – Two girls grow up in different circumstances. One becomes Britain’s first elected head of state; the other chooses an ordinary life. Both are free.

Big Dreams, Little People: Ceremonial Presidents – Highlighting democratic role models like Iceland’s first female president and Ireland’s Catherine Connolly, without portraying privilege as sacrifice.

Kids Against Kings – A cheeky, rebellious take on power, though we’re mindful that being “against” rather than “for” may invite backlash.

We’re still brainstorming — and we welcome ideas and drafts.

This time next year, our book could be in print and online, helping free young minds and inspire the citizens of the future.