Indifference Is the Crown’s Greatest Ally — Here’s How to Take It On

12/22/20255 min read

Complacency and disinterest in the monarchy among many British people can be understood as a response to several psychological, social, and political factors that make the issue feel distant or irrelevant to everyday life. Here's a deeper look:

1. Lack of Personal Impact

For many people, the monarchy doesn't seem to affect their day-to-day life. Most people aren't directly involved with or impacted by the Royal Family's actions, and the monarchy doesn't play a tangible role in their personal or professional spheres. This sense of detachment can make the institution feel like an abstract concept, something that exists mostly in the background of British life. As long as the monarchy is not causing harm or engaging in controversies that directly affect people's lives, there’s little incentive to push for change.

2. Perception of Stability

The monarchy is often seen as a symbol of stability in a world that is constantly changing. For many, this historical institution represents continuity and a connection to the past. With the rapid pace of political and social change such as Brexit, many people may feel that the monarchy offers a sense of permanence. In this context, the idea of abolishing the monarchy could seem like disruption, leading to complacency about the need for reform.

3. Low Priority in Daily Life

In a society with many pressing issues—such as economic challenges, healthcare, education, and social justice—many people may not see the monarchy as a top priority. Political and social activism tends to focus on issues that are more immediately relevant to people's lives. This leaves the monarchy largely off the radar for many citizens who may be ok with the status quo, seeing other issues as more important.

4. Perceived Futility of Change

Another factor contributing to complacency is the perception that abolishing the monarchy would be a complex, costly, and possibly divisive process. The institution is embedded in the UK's constitutional structure, and any move to abolish it would require legal and political upheaval. For many, this creates a sense of futility—why bother challenging an institution that may seem to work fine when there are so many other political battles to fight?

5. Psychological Distance

There's also a psychological aspect to complacency and disinterest in the monarchy. The Royal Family is often perceived as being a distant entity—both physically, living in palaces and estates, and symbolically, as an institution that stands apart from the realities of everyday life. This "us vs. them" mentality fosters the view that the Royals are not part of the same social or economic system as ordinary citizens. They become so remote from daily concerns that people simply don't think about them unless there's an event to draw attention, like a royal wedding or a scandal.

6. Skepticism Toward Political Activism

There's a sense of resignation in some corners of society. The lack of widespread opposition makes it hard to rally support for the abolition of the monarchy..

So what can we do to convince people that our cause is worth fighting for? That our cause is their cause too?

1. Education: Turning Indifference into Understanding

Apathy often grows where knowledge is thin. Many people are not actively pro-monarchy; they simply don’t know why it matters enough to oppose it. Education is therefore foundational. This means explaining what the monarchy actually does, how it is funded, and how it fits into modern power structures.

Crucially, education should move beyond symbolism. The monarchy is not just pageantry; it represents inherited privilege, constitutional inequality, and a barrier to democratic reform. When people understand the real political and economic implications—such as public funding, lack of accountability, and its role in entrenching class hierarchy—apathy becomes harder to sustain.

Education also involves dismantling myths: that abolition is unrealistic, destabilising, or somehow “un-British.” History shows that political systems change when people are informed enough to imagine alternatives.

2. Providing Examples to Follow: Showing That Change Is Possible

One reason apathy persists is the belief that “nothing else works.” Real-world examples challenge that assumption. Countries that have peacefully transitioned away from monarchy demonstrate that abolition is neither radical nor chaotic—it is practical and achievable

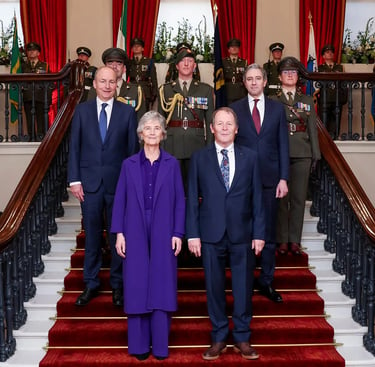

Catherine Connolly became Ireland's 10th President this year

Ireland offers a particularly relevant example. Once under the British crown, Ireland is now a democratic republic with an elected, ceremonial head of state. Its transition illustrates that national identity does not collapse without a monarch; instead, it can be reshaped around popular sovereignty and accountability.

Examples like this turn abstraction into reality. They help people move from passive disengagement to active consideration: if others have done it, why not us?

3. Bringing Young People On Board: Shifting the Cultural Centre

Apathy is weakest among those who feel the least invested in existing hierarchies. Young people, who already face economic insecurity, housing crises, and climate breakdown, are less likely to see inherited privilege as legitimate or relevant.

Engaging younger generations means meeting them where they are—on social media, in schools, universities, and cultural spaces—and framing abolition as a future-facing issue. The monarchy often feels like an institution preserved for nostalgia, not necessity. Highlighting that disconnect makes abolition feel less like a fringe concern and more like common sense.

When young people lead, movements gain energy, creativity, and long-term sustainability. Even if immediate change is slow, generational shifts steadily erode apathy over time.

4. Working With Allies on Aligned Causes: Making Abolition Relevant

Apathy thrives when issues feel isolated. Abolishing the monarchy can seem abstract unless it is connected to struggles people already care about—democracy, racial justice, economic equality, media reform, or decolonisation.

By working with allies across these movements, abolition becomes part of a broader push for fairness and accountability, rather than a single-issue campaign. For example, discussions about wealth inequality naturally raise questions about untaxed royal assets; debates about democracy expose the absurdity of unelected power.

When abolition is framed as relevant to everyday injustices, it stops feeling distant or symbolic. It becomes practical, urgent, and worth attention.

5. Emotional Appeal: Making People Feel Why It Matters

Facts alone rarely defeat apathy. Emotional engagement is essential. The monarchy survives not because people rationally defend it, but because it is wrapped in sentiment, tradition, and spectacle. Countering that requires emotional narratives of our own.

This means telling human stories: families struggling while public money funds royal estates; communities excluded from power by birthright; citizens taught from childhood that some people are simply “born to rule.” These stories help people feel the injustice, not just understand it intellectually.

Emotional appeal does not mean anger alone—it can also involve hope. The idea that everyone is equal, that leadership should be earned, and that society can move beyond inherited power is deeply motivating. When people connect emotionally, apathy gives way to conviction.

Apathy toward the monarchy is not approval—it is disengagement. By educating the public, offering real-world examples, mobilising young people, building alliances, and appealing to emotion as well as reason, that disengagement can be transformed into momentum. Abolition becomes not just possible, but relevant, relatable, and necessary.